Deadly Nightshade

“The plant bears these beautiful dark, purple berries. But if we just let them go, they grow up and crush the life out of the plant.”

“The plant bears these beautiful dark, purple berries. But if we just let them go, they grow up and crush the life out of the plant.”

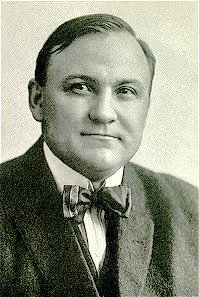

Hannah Lowe speaks about the great evangelist Paul Rader’s vision of his own heart apart from God and how he found victory. She then spoke about the only way to handle our sinful nature and likened it to the poisonous deadly nightshade plant. This took place in a meeting on Sunday, October 15, 1972.

“Paul Rader knew what he was talking about with his hymn, and he got the victory there, and he did not rest until he got rid of self and what was in there.”

Paul Rader. Praise God, beautiful. He knew what it was to have the life of victory. And I remember when he told part of his story, I think I’ve told it here, that after he came out of seminary, I don’t know which one, he knew that he had lost Christ in the seminary. He lost Him, left Him in the seminary. And he was miserable. He went to Europe, I don’t know how long he stayed. I know he had a praying mother and father, and the mother and father—I think it was the mother that was dying, and her boys were out of Christ. There was one son Luke, and she said, I can die because I have the assurance that my sons will come through, and they weren’t through. But they did come through. And he went to Europe, I think he was somewhat of an artist, but he was very miserable.

He came back to New York, and he knew that he had to get right with God. So he went into a hotel and prayed and he said that he would not eat. He would allow himself no food until he came through with God alone in his hotel room. And there as he prayed, he had a vision of his own heart, what it was filled with. And it was so vile and black that as he vomited and vomited, black came into the vomit. It was so bilious and vile, and he vomited that out. And he had victory when he stepped out, and it was then, that the Kaiser was fighting. And he put up—or if was after that, anyhow—he put up this sign on the street, somehow, right out on the street he started, well, is the Kaiser the anti-Christ?

That’s how he started. And the people came by the hundreds in New York downtown, I think Columbus Circle. By the way, we preached at Columbus Circle years ago. And he preached and had the crowds, and that’s how he started. He came to have the big tabernacle in Chicago. But you can see that he knew what he was talking about with the hymn, and he got the victory there, and he did not rest until he got rid of self and what was in there. The vileness, the bile, off of the whatever was in him. Vomited it out. Just vomited, literally vomited the hatred and the putrefaction, all that he had, that he knew himself to be. Out with it.

He took the victory and got it, and became a mighty man of God. Praise God. Paul Rader, he’s in glory. But what he does, or what he was, lives on. Praise His Name. So, you would have to settle it. You’ll have to settle it. At times, it can be just like that. But in many cases, it is not settled. And the misery of it all is so portrayed in the features in the face, all that there is not, in the depths of that heart, the victory. And all this painfulness and the chopping off of the peace. I’ve heard people say that, you don’t pick the chicken alive, and pull out each one of his feathers and cause all that mortal pain.

But you cut his head off first, and then you scald him and pick him. But most people are trying to pick him alive. Pick yourself alive. And you cut a little of this off and you pull a feather off of envy and you pull out of strife and what’s that emulations in the midst. All these different things that Paul names. But emulations and strife is just as bad as the whole category there. You have a whole category of what are the works of the flesh. Of course, the fruits of the Spirit are, but the works of the flesh are listed: envyings. And why do these envyings keep going? Why are they? Why do they keep going? And why does the strife keep going? And it is such a pain to live with such people and live around such people.

Such a thing, well. Say one of the two or however many it be have the victory, it can be that to kill you. Kill you more, until you have no feeling about it. So a person that is under it, and they have to be, they can’t win out, in the sense of letting it kill them off. And die out to it. But, for the most part, it is so terrible, the strife. You can understand when Sarah said to Abraham, “I can’t make it anymore with Hagar.” To begin with, she’s not of the royal seed, that is, the seed of faith, the child isn’t. And there’s strife, and Ishmael has arisen and probably torturing and tempting the son of faith.

And Paul uses it as the allegory, cast out the bondwoman and her child because as we know it hurt Abraham, because he was the same one that brought into the world, the child of failure, Ishmael. But when he questioned the Lord, the Lord said, Sarah’s right. Cast out the bondwoman and her child. For them ever to have the right setting in the home, to have the right set-up in the home. And there’s where the rub comes, with whom you live, with whom you’ve been brought into contact. And it does come to the place.

But if you would see then Abraham and Sarah fail, but you don’t. The right ones come forth. Out of the way the weeds, just like we have to take the fields or the garden to get the weeds and the choking because they grow higher and faster than the real plants that you want. I had to smile. There is a weed called Deadly Nightshade. And during the summer we’ve had some of our plants outside. And I noticed that scarcely any of our boys know anything about weeds. They would have some of the weeds grow up like this, and they would think—they haven’t cared through their life. Of course, many might not have had the privilege that I had of having a grandmother that cared for plants, and I’d be in the garden with her, and I knew what weeds were.

I suppose I helped her weed as she couldn’t stoop very well. I suppose I learned, is this a weed or isn’t? If I hadn’t, I would have wanted to know. I went to the country every summer, and I wouldn’t know what every field was or every plant, if I didn’t know, I would ask. Now those are potatoes. That’s how I know today what are potatoes and tomatoes and turnips and all of those, in general, I don’t know everything, but in general. Just a common knowledge. And we came to the place where the plants could get too cold, so just bring them inside, just have to set them on the floor in the sun parlor for the time. But I just rushed out the other day and had Mark to help me to get them sitting around in some kind of manner.

Well, one plant there was very small, I don’t know which one it was, but the Deadly Nightshade was about this high, and it had berries on it. Doesn’t it? It has red berries. Mark saw it, I explained it all to him. Now if you eat one of those berries, you die. [They have strychnine in them.] And I imagine that, different ones as they looked at it, if they ever noticed it, would think, well, now that’s nice, she has a plant there that is bearing these beautiful dark, purple berries. [The flower is purple, and berries first are green and then they turn a very nice red.] Very nice red, and they turn about this dye to the ripeness of it. Just to think, if somebody had gone by there, and had said, that’s nice, just want to taste that berry, well, you would have been on the floor. Found you on the floor, gone. But no one knew that.

Because they hadn’t paid any attention, they don’t know what a weed is, they don’t know what deadly nightshade’s shade is. That is why I call it shades of night. Deadly nightshade, oh my. That’s it. We just let these things go. They grow up, and the little plant was how high? It was just about dead—it had crushed the life out of the plant. But nobody during all the summer months would know, well, that’s the deadly nightshade. You would have known it, wouldn’t you? I think you showed it up in Martha’s Vineyard. [man: Well, where I grew up, it was on my grandparents’ farm. There was always a place on her farm where this deadly nightshade grew, I was actually afraid to go near that place as a boy where it grew, because I had always heard if you eat it, it will kill you. And I showed it to Hannah last summer out there at Martha’s Vineyard. And then this past summer at Rehoboth, I was walking out around by the back fence, and I found some of it there. It’s not an uncommon weed, it’s fairly common. But as is the case with many plants, it has amounts of strychnine in them. Now it just happens that deadly nightshade has a larger amount than, for example, like an apple. An apple seed actually has strychnine, very little. But deadly nightshade has considerable…] concentrated.

Concentrated poison. And as I was talking to someone yesterday, it all came, it’s so plain. Yet it came all so plainly again to me.

That you can boil it all down to a nutshell, put it in a nutshell, just the kernel. And put it right down to the core, and that’s what it is, you refuse to die to self. Very plain. You don’t have to doctor it or… Refuse to die: it’s what I want. And it’s so easy to dole it out to someone else and say, don’t do this, or a set of don’t’s, or a set of you can’t’s, or a set of this… But you’ve got to cut the chicken’s head off and not play it out feather by feather. You wouldn’t want to see the chicken suffer, feather by feather. You want to have… You’re going to kill him anyhow. Why not knock him in the head to begin with? And then pull out the feathers. That’s why, oh, it’s so sweet to die with Jesus. It’s so sweet to live with Jesus. And because you are in such a condition, you are holding on to something there, conscious or unconscious. Because you couldn’t be in this condition. You could point others out, as well as you. You couldn’t be in this condition, if you wanted everything of the Lord and not yourself. Something in there is holding you back.

© 2026 Harvest Gleanings.